Bed Piece

BED PIECE

“In 2011, I dreamed of making a circuit that would sonify the discovered plurality of a sexual encounter. The frame for this artwork was thus the bedframe itself, where many of my intimate experiences have occurred. I wanted to make a passive piece, one that would make music when I was with someone, but not require the gestures of an instrument. I didn’t want to put music in the background, but rather allow it to be absorbed by the larger, more glacial pace of our every- day movements over many months. But I wasn’t in a relationship at the time—it occurred to me that most of my nights were not spent having wild casual sex, but being by myself. I wanted to make a piece that would sound when with a partner, and would be silent when I was alone.” (excerpt From Histories of Bed Piece)

- Inner Detail

- Synthesizer Detail

- Wide Shot

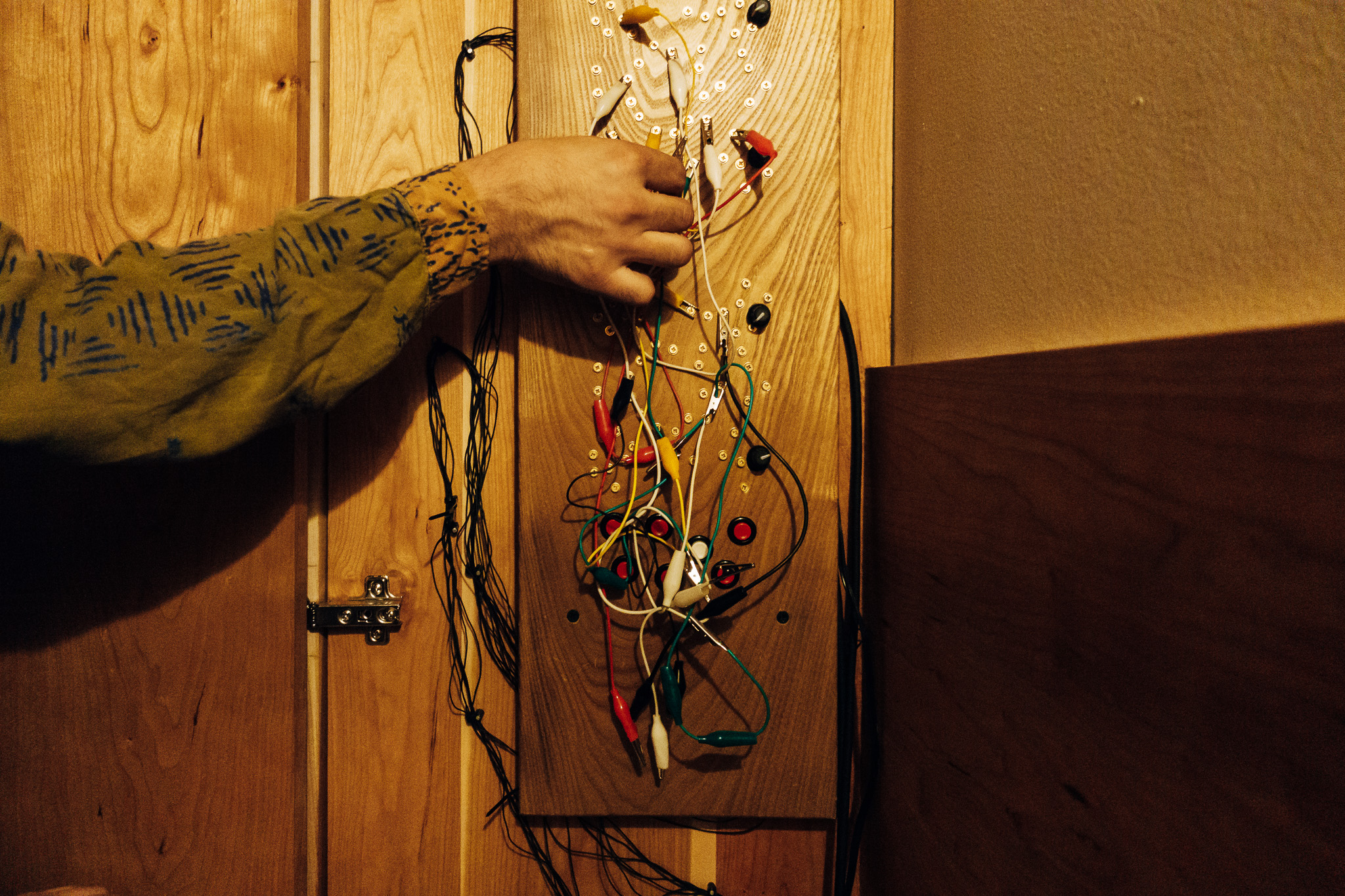

- DF on Bed Piece

Bed Piece is an idea, and a series of sonic objects, about intimacy and solitude. In the beginning, the idea of Bed Piece was solely conceptual, because while I had a very elaborate feeling about how I would interact with the thing in my life (and of course, with it and other people…), it took some time to figure out its technology. There are three pieces described here in pictures and words: Bed Piece (2011–15), which is the kind of framework that predates its subsequent physical iterations; Rehearsal for Bed Piece (2014), which was its first sonic iteration, and Bed Piece: Pelta Feldman Variation (2015), the eventual commission by the Williamsburg artist residency Room & Board. While I finished the circuits for this piece in 2014, I never made a public presentation of the work, which seemed too private to share. The original piece that I imagined—a one-year performance in which the bed synthesizer is turned on every night—remains un-performed. In keeping with the privacy of this piece, no sound or video is documented, only pictures and the suggestion of an idea.

On this page, you can read the story of Bed Piece in reverse, first with the pictures of the Pelta Feldman Variation, and the words I wrote for its unveiling party in 2015. You can also read the contents of the zine we published for this occasion. Usually I’m a little loathe to have so much text on a webpage, but I feel strongly that I shouldn’t break the continuity of the essay. After this, I’ll post some pictures of the making of the commission, as well as my earlier experiments.

Some Histories of Bed Piece

Daniel Fishkin, 2015

In 2011, I dreamed of making a circuit that would sonify the discovered plurality of a sexual encounter. The frame for this artwork was thus the bedframe itself, where many of my intimate experiences have occurred. I wanted to make a passive piece, one that would make music when I was with someone, but not require the gestures of an instrument. I didn’t want to put music in the background, but rather allow it to be absorbed by the larger, more glacial pace of our everyday movements over many months. But I wasn’t in a relationship at the time—it occurred to me that most of my nights were not spent having wild casual sex, but being by myself. I wanted to make a piece that would sound when with a partner, and would be silent when I was alone.

I thought about this work for a long time. As I began working on different solutions and different circuits, I thought also about different ways to share this experience with a partner or an audience at large. Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh undertook a very intimate piece with Art / Life: One Year Performance 1983-1984 (Rope Piece), in which they were tied together with an 8-foot rope for a year. As the piece continued, they used several approaches to documentation: a photograph every day, and a C60 cassette recording their daily conversations. While they shared these pictures along with the work, they sealed away the cassettes forever, never to be listened to. Should I take a picture of my bed, each morning or each night? Should I use a polaroid camera for its immediacy, or is that painfully dated in this day and age? Should I make recordings, or should these bedroom performances remain “live”? I talked about these fantasies with new partners, sharing them at first with great reluctance, as one would reveal an STD. I really believed that a relationship with me would also mean a relationship with Bed Piece.

CleveMed Medical Devices provided me with some samples for bed sensors (for preventing bedsores in hospital beds), but this technology was stubborn and prohibitively expensive. I also considered using an infrared camera to control software via Max/Msp and Jitter, but I wasn’t happy with my software sketches at the time. And, something about having a camera over my bed felt weird. This project is about intimacy, not surveillance or voyeurism.

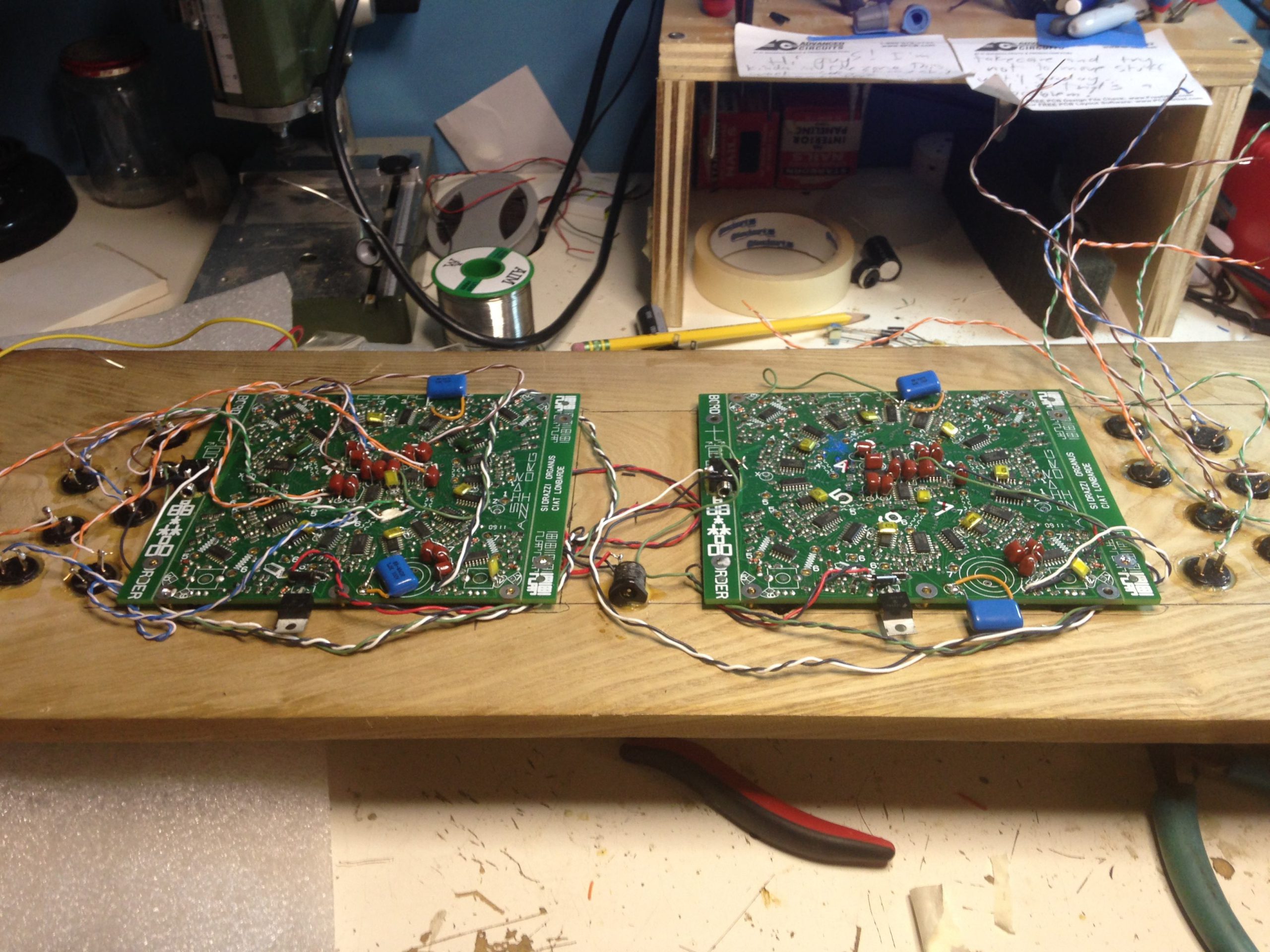

The solution came in the form of a synthesizer. I mentioned the project to my friend Peter Blasser, who is a synthesizer designer at his own company Ciat-Lonbarde. I want to mention the origin and context of these synth circuits. Recall the early video synthesizer designs by Nam June Paik—do ever we consider their engineer, Shuya Abe? In 2010 I worked for Todd Bailey, the engineer who designed the circuitry behind many of Cory Arcangel’s works. Bailey’s name is listed nowhere but the internal circuit boards and payroll invoices. I’m interested in engineers and the subtleties of their role in what I find to be very compelling, important works. I want to cite my sources, but it’s more involved than that. The technology is not neutral! It bears on the work; it defines its formal qualities. The work would mean something different if achieved by different means, by a different circuit or sound. When I discussed this piece with my friend Monroe Street, he suggested a version of a Bed Piece that contained only sounds of laughter. Ha ha!

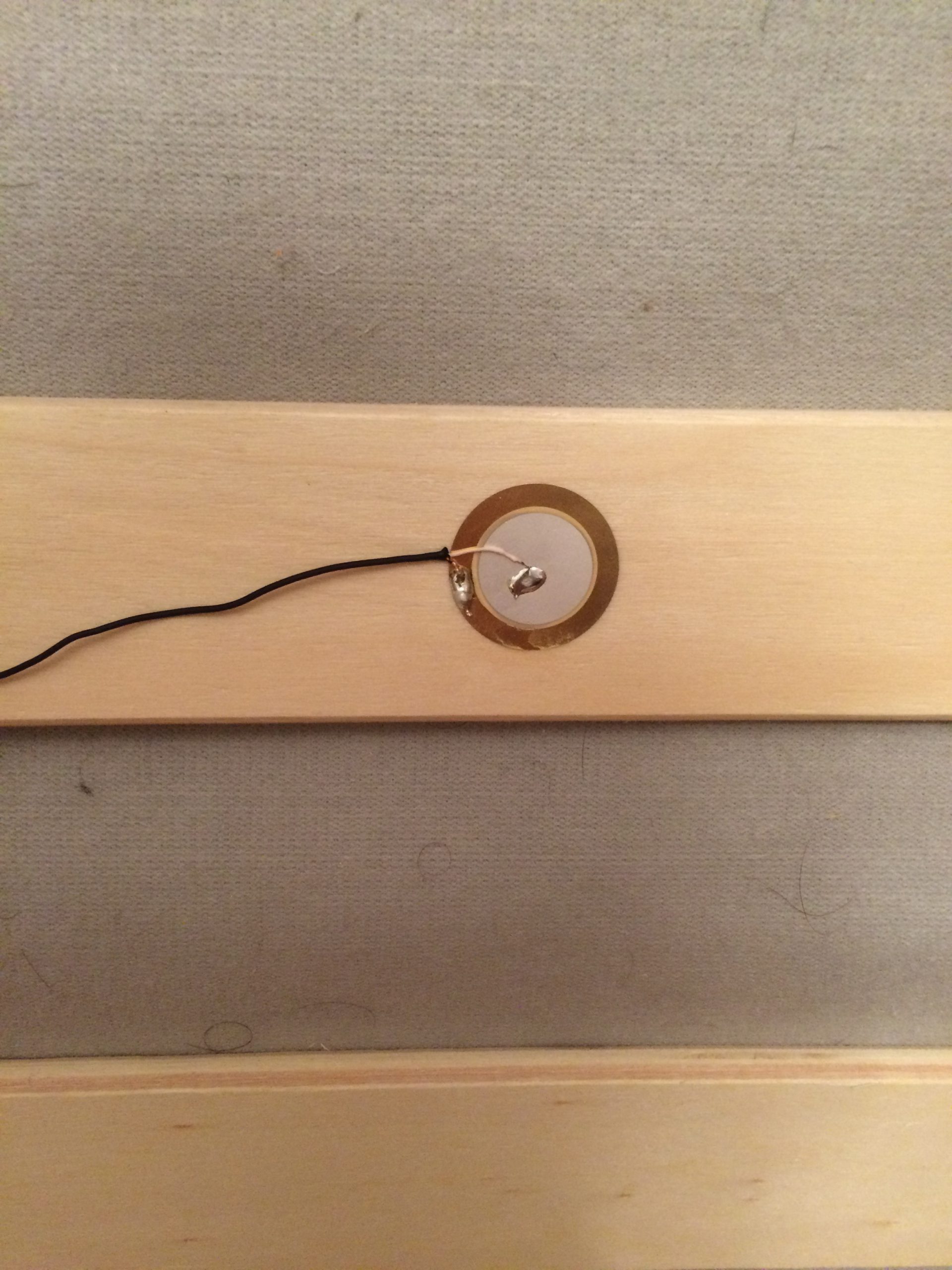

Most important were Peter’s words: “You don’t want to have your computer there while you’re in bed with someone.” Peter gave me two Sidrazzi synthesizer circuit boards and I built them into a bedside table made from cherry and wenge wood. Julia and I bought a bed off craigslist. 14 voltage-controlled amplifiers for triangle waves are controlled through contact microphones affixed to the wooden bed slats. This was the first time I created a tangible object that would actually allow me to perform Bed Piece, to hear it, to experience it. The Sidrazzi synth is not adjusted by pitch knobs or set to tempered intervals, but by buttons and brass pegs that produce an unexpected response. The sound is always evolving, even more so as you stumble across the bed and discover different regions of sound. There is no tuning for Bed Piece—rather, playing it is a continuous process of tuning.

During my residency at Room & Board in 2014, I set up the structure that for me felt like an adequate rehearsal, but certainly not the piece I had imagined. It was not my room, not my home, and thus doing the piece there seemed strange—exciting, or even pleasurable, but a contradiction in my own terms. During the opening salon, I invited people upstairs in small groups—why not try it? I was appalled by a visitor who spanked his girlfriend performatively in front of a room of strangers. However, not all of these contradictions were unwelcome. While having sex on the bed produced a predictable sound, I discovered that actually the moments before and after love-making were truly interesting, each player/performer carefully adjusting their weight and listening for their sonic impressions together in time.

Back in Connecticut, where I was in graduate school for music composition, I set up Bed Piece again, and everything seemed ready to go. But I only turned on the circuit occasionally—I never began the yearlong commitment I had dreamed of. At first I thought, well, who knows where I’ll be when June rolls around and I graduate from Wesleyan—so it was the wrong time to start the piece. But somewhere between there and falling in love with my sweetheart, Catalina Alvarez, I never actually began the piece that seemed to be so fiery and necessary back in 2011. The work would have a different meaning now that I’m no longer single. We set it up the circuit in our home in Philadelphia, but never turned on the speakers. The microphones are still listening, making voltage in response to our changes in pressure. I think about that often while we’re lying there.

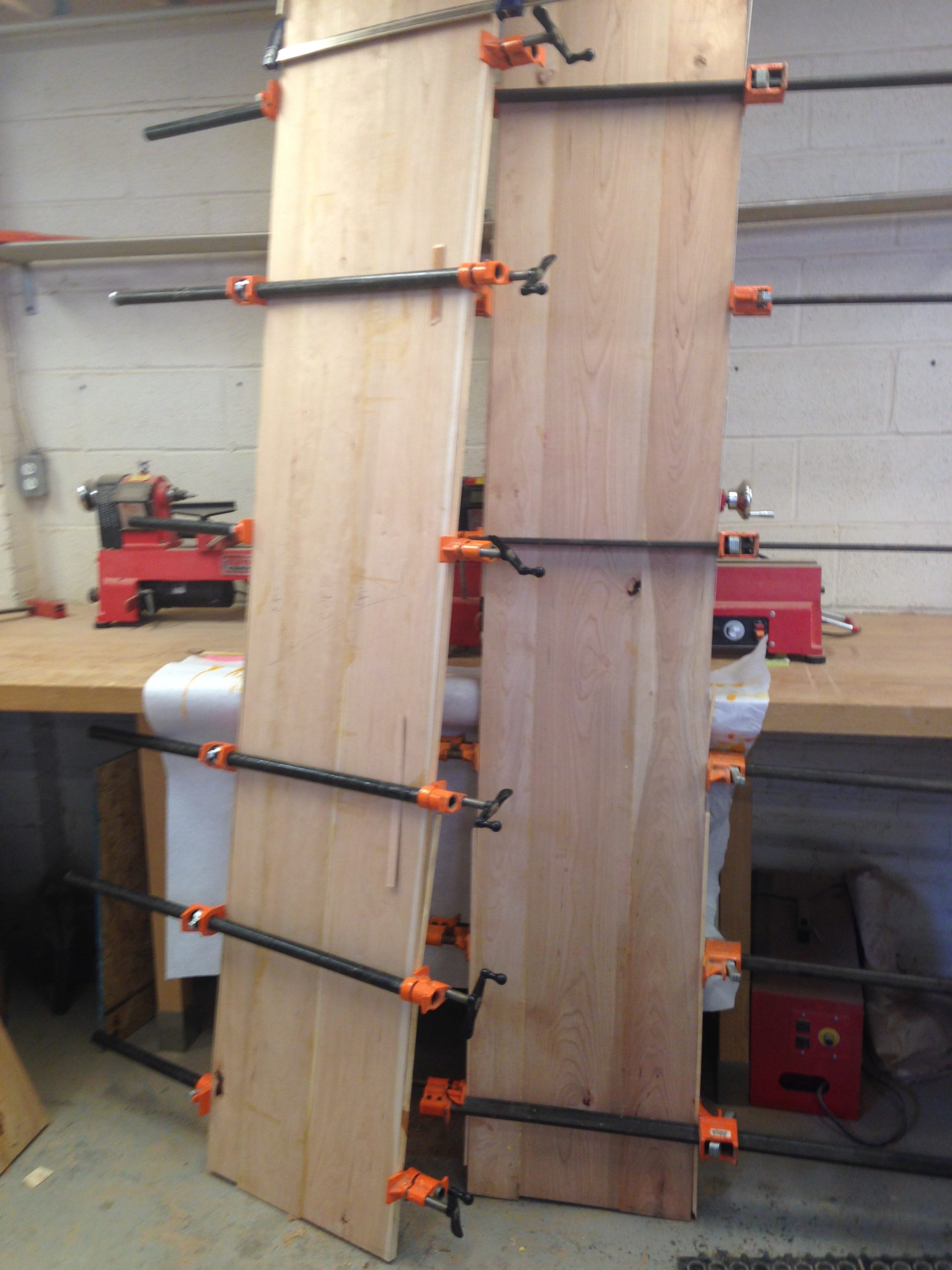

Anyway, I’m not sure I remember how it came up to reinstall this piece at Room & Board. Maybe Julia had mentioned that she hoped to have a Murphy bed for the guest room. When Julia and I first began to seriously talk about doing this piece again, we began to talk about it as a permanent work, an addition to her and Hannes’s house and the artistic project she now spearheads. This new piece, the so-called Pelta-Feldman Variation, is largely determined from serious aspects of practicality and community. It is no exaggeration to say that Julia was a major collaborator in formal terms. We spray-painted the bedframe, purchased from murphybeds.com, matte gold. We picked cherry lumber to match the desk already in the room. Every aspect of the work was measured carefully in order to insure that it would not disturb the existing furniture and architecture. Our ongoing conversation about lighting continues.

Besides having the occasion to make something beautiful for someone who will care for it, I don’t really know what the Variation means to me as a sonic object—who will play it, and when, and why? One very valuable aspect of making the piece was the occasion to think about the ideas of this piece seriously, to treat them as real considerations, while the original idea remained untested. I still believe in the piece, and I hope this object can tell a story.

We only turned on the amplifiers on Tuesday. Most of the time, as I worked on the piece, the circuit was not sounding. Without wanting to feign neutrality about my choice of sonic materials, I must confess to a fundamental ambivalence about the porous boundaries between sound and music that create the vehicle for this artwork to exist. Music here is a tool for measurement, not mere sonic content. When I give a one-liner about this piece—if someone asks me what I’m up to lately, for example—I always reduce it to “I’m building a bed synthesizer”—and I feel bad at the deception. I don’t want to play the bed synthesizer; I want to hear how people sound.

Every time I undertake a major work I’m a little bemused by my dominant visual aesthetic that emerges in the form of a thousand wires. Over 200 feet of electrical wire was used to transform the bed from static object into something more. They are everywhere. They are difficult to control, and to untangle. But, I like the wires. I can’t hide them. The circuits are messy. The wires are how you connect things. I want to feel connected.

- the murphy bed that we bought

- Glueing up the cherry panels before asesembling the frame

- The 14 voice sidrazzi synthesizer I used for the

- Beginning to wire the instrument

- continuing to wire

- getting a little tired from wiring

- checking the dynamics of the sound and interaction

Well, there’s more…

but that’s…