TO THE PRINCETON SOCIETY OF FELLOWS SELECTION COMMITTEE:

As an artist in academia, I occupy a unique position of knowledge production. Not everything that I do can be presented in the traditional methods of scholarship, such as paper and journal publications, and conference attendance. The art I produce itself has epistemic value, and speaks more directly to my research interests and publication history. Therefore, I made this page because sometimes, pictures or videos describe the work more clearly than my text proposal.

1) Composing the Tinnitus Suites

[vimeo width=”460″ 401762264]Composing the Tinnitus Suites: 2020 (excerpts)

(2020) 3:52

I want to compose music that makes tinnitus desirable rather than hated or feared. I do not want to get used to my hearing damage—I want to use it.

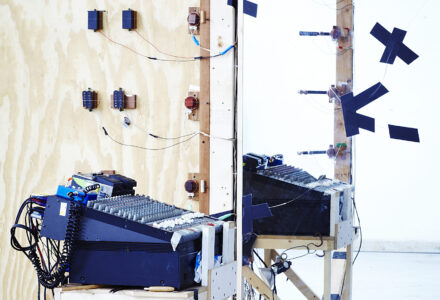

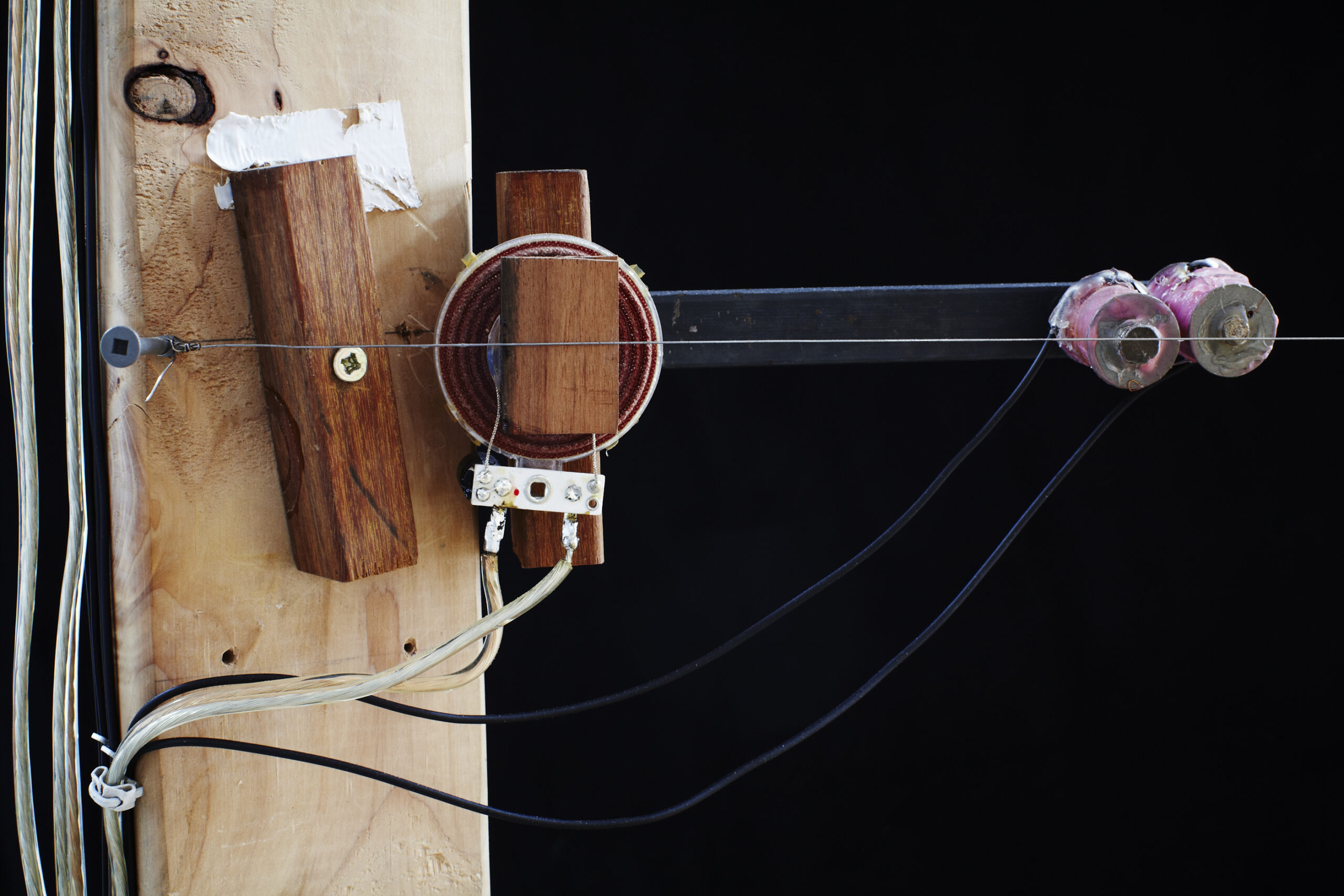

During a residency in 2011, I created a system of tensioned twenty-foot long piano wires activated by mixer feedback; I could sustain its tone infinitely, using guitar pickups and pressure transducers to coax the strings into vibration. I called it Lady’s Harp, named in tribute to Ellen Fullman, Maryanne Amacher, and the ancient Greek Aeolian harp, whose strings are set into vibration by the wind. I have made five iterations of Lady’s Harp, and in each version I connect the strings to the walls or floors, turning the room into the instrument’s resonant cavity. Once I showed the piece to a neuroscientist, and she remarked that it functioned as a mechanical model of the inner ear. I had stumbled upon the perfect vehicle for Tinnitus Music.

[vimeo width=”460″ 197700671]Composing the Tinnitus Suites: 2016 (excerpt)

(2016) 14:29

featuring Cleek Schrey (Hardanger fiddle) and Ron Shalom (contrabass)

This version of CTTS was presented in Philadelphia, PA, Fall 2016, as a part of a project grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. It showcases a collaborative composition made with Ron Shalom and Cleek Schrey. I had never combined the Lady’s Harp with conventional instruments before 2015. Maybe it was hard to let others inside my tinnital world. It had always seemed like such a private thing, the Lady’s Harp—to explain how it worked and the sounds I wanted to come out of it was almost as difficult as explaining precisely what the ringing in my own ears sounded like. Which, of course, is impossible—tinnitus is a neurological hallucination—it doesn’t exist in the physical world.

So, beyond the WHAT of tinnitus, is the WAY of tinnitus—a perilous synergy—the excess that lingers in our perception, the buzzing sustain afterwards, and, wondering what sound is causing what effect. It was like the boundaries between our instruments were breaking down—Cleek would bow a note on the fiddle, and a note would sing out on my Harp. Ron’s end-pin scraping the floor would cause deep bass swells. Their own melodic cascades intertwined, crossing ranges, enveloping each other’s registers. I lost track of where the sounds were coming from. Ron? Cleek? The Harp? Inside me? Perhaps we became each other’s tinnitus.

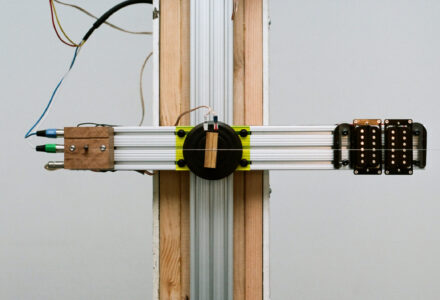

- transducer detail (2014)

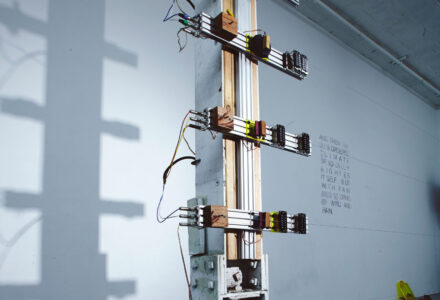

- installation (2014)

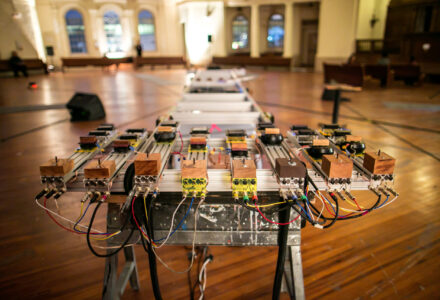

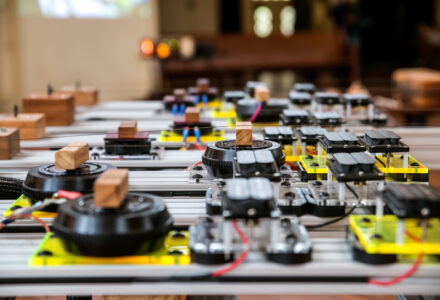

- freestanding version (2014)

- pickup detail (2014)

- freestanding version (2014)

- installation (2012)

- transducer detail (2012)

- installation (2012)

Masking Songs (excerpt)

(2020) 2:00

Masking Songs deals with the principle of auditory masking, in which the perception of a sound is affected by another sound. In lieu of a medical cure for tinnitus, auditory masking/suppression is one of the primary means for attenuating the perception of phantom sound. However, depending on what one is trying to mask, from the sounds of the acoustic world to the phantom sounds of tinnitus, the means of sound occlusion are formally distinct.

Obfuscate and discover the conscious music-making activity of other players. The primary goal is to achieve suppression and “unveiling” of sound you create. Tinnitus Scholarship terminologizes this relationship as “signal vs. masker”: signal is the ever-insistent phantom perception of tinnitus, and the masker is that which can suppress it—acoustic sound.

Masking Songs Click here for the score!

[vimeo width=”460″ 289409928]

Composing the Tinnitus Suites: 2008-2011 (mise-en transcription) (excerpt)

(2015-2016) 2:00

This piece is a transcription of an earlier work, Composing the Tinnitus Suites (2008-2011), which I created on the Lady’s Harp. I wanted to test whether I could make work in the series of my Tinnitus Suites project, but without needing to do a site-specific sound installation. Also, I felt the original recording calling to me in its tonal clarity. Using Fourier analysis, I approximated the harmonic content of the Harp’s strings and transcribed it for the six instrumentalists of ensemble mise-en. This work could have been done more quickly with a computational process, but I did it all by hand, and savored the chance to slave over each measure. Though I used my computer to do the Fourier analysis, I only wanted the ensemble to play what I was able to hear, and bear responsibility for the notes I selected from the spectrum of the original piece.

Composing the Tinnitus Suites: 2008-2011 (mise-en transcription) Click here for the score!

2) The Daxophone

- the A group

- most of these are scroll sawn.

- daxophone parts (2016)

My entry into experimental music started with the daxophone. The daxophone, created by Hans Reichel, is a more elegant construction of the instrument every child discovers when they put their ruler off the edge of their desk and pluck it: BOING! When that ruler is played with a cello bow, it produces a much different sound: a very vocal, vowel-ed tone that could easily be mistaken for another instrument or animal. One cannot buy a badger-cello, so I learned to build my own. I noticed that every piece of wood sounded unique, and I could control the instrument by altering its shape.

[vimeo width=”460″ 371052427]In the Daxophone Workshop

(2019) 3:04

Since 2005, I’ve always built daxophones in my itinerant workshop, meaning, wherever I happen to be, with a slew of hand tools and whatever else is in front of me. This process has changed a lot over the years, so this is what it looks like today. In 2019, a residency with The Daxophone Consort (Cleek, Ron, and me) brought me to the Watermill Center in Long Island, NY. The residency was a focused time for playing together. As the days passed, I made sure to spend at least a few hours in the daxophone workshop.

[vimeo width=”460″ 358230818]The Daxophone Consort

(2019) 2:00

A consort is an ensemble whose members all play the same instrument. Since 2016 I’ve been working with a consort of daxophonists to stretch the boundaries of what is typically possible on this instrument. Ron Shalom and Cleek Schrey each bring a personal history of string techniques to the daxophone, including the conservatory and old time music. We are currently the only known extant daxophone consort!

No-lone Zone

(2015-17) 2:38

No-lone Zone is composition for daxophone based in an interpretative language of sonic cues. There is no linear structure, and improvisation makes up build of the material, yet a shared language guides the music to and fro. There are a number of “audio logos” which performers can recognize in a thicket of activity—a forte pluck or whack of the daxophone, a endlessly long glissando up (or down), and a fast col legno tremolo of the bow trilling against the wood of the instrument. These calls tell the other performers that it’s time to end one section and begin another. The changes occur when all players perform the cues in unison—thus, a player can prolong the current musical moment by refusing the cue.

No Lone Zone Click here for the score!

appendix: transcriptions & other work

[vimeo width=”460″ 113327193]

Pendulum Music (Steve Reich)

(2014) 10:54

Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music is a classic feedback piece from the early days of minimalism and process music. Old pieces of the avant-garde can seem dusty, but feedback, which is unique in each instantiation and each resonant cavity in which it is found, should never actually get old. I wanted to add another wrinkle in the story of this piece, and so shifted the medium from sound to light. Instead of speakers, I use oscilloscopes, and instead of a microphone, I use homemade light microphones made from photodiodes. Besides this, the basic structure of the piece is unchanged.

[vimeo width=”460″ 353639460]Ryoanji (John Cage)

(2014) 2:58

In 1983, John Cage began a composition-in-progress called Ryoanji, based on the famous stone garden in Kyoto, Japan. The garden contains fifteen stones of different sizes laid out on raked sand. John Cage wrote the piece for percussion and any number of soloists: oboe, voice, flute, contrabass, and/or trombone. The dry, repetitive percussion represents the raked sand. The solo parts are graphical scores derived from Cage’s tracing of various stones, so that all the solo parts exclusively produce glissandi. Cage never wrote any music for daxophone, but the daxophone captures the microtonal essence of the piece. The daxophone is resolute in its refusal to intonate precisely. Thus, the attempt to produce a linear glissando with the dax produces a notched gurgle, a broken curve that might resemble the outlines of the rocks in the score.