TO THE NYU SELECTION COMMITTEE:

This page covers three major areas of my artistic output: the aesthetics of hearing damage, the translation of light to sound, and my experimentation with the daxophone. In each case, these are projects that span many years of research, so multiple images and videos are presented to be representative of the entire work area. If you’re curious, I’ve also included an appendix that includes interpretive work, and other projects that don’t fit the categories described above.

1) The Daxophone

- the A group

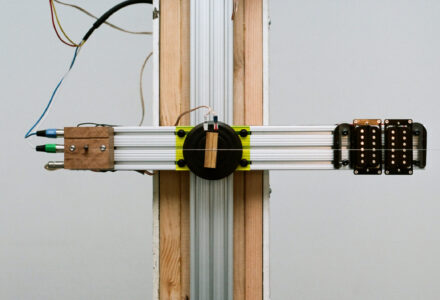

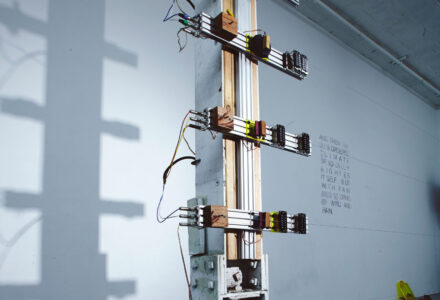

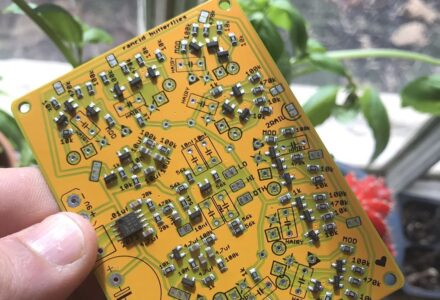

- daxophone parts (2016)

- most of these are scroll sawn.

The daxophone is a thin wooden strip played with a bow, which was created by the German improviser/inventor Hans Reichel in 1987. I discovered it in 2006, and was drawn to its uncanny vocal timbres— somewhere between a cello and badger. One cannot buy a badger-cello, so I learned to build my own. Since then, I have built hundreds of daxophones, each with its own melodic voice.

In the Daxophone Workshop

(2019) 3:04

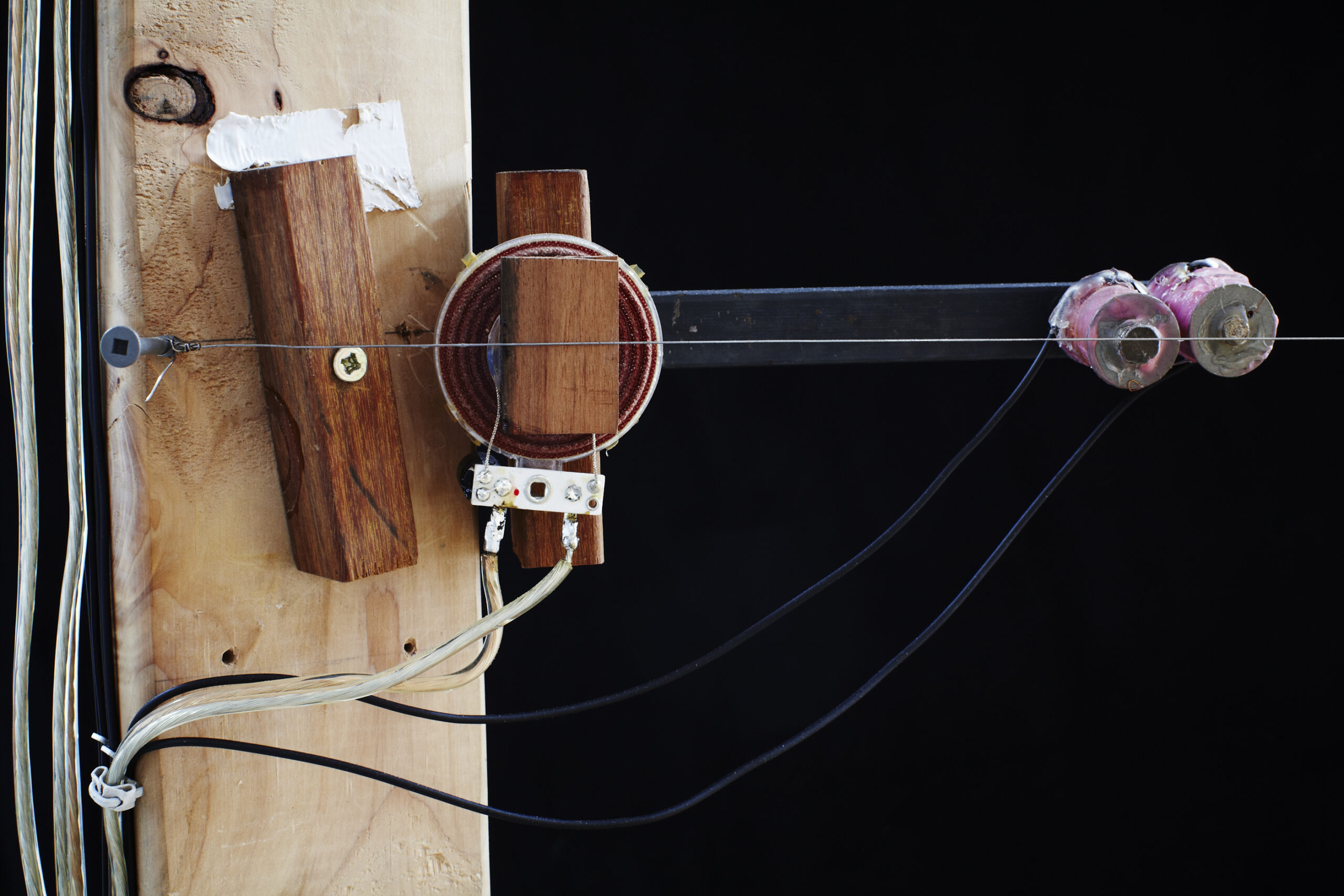

The daxophone is literally only wood—no strings or air columns. Thus, every change you make to the wood changes the sound. The essence of the instrument is a vibrating tongue, anchored at one end. Its other parts are tools to resonate that tongue (bow), amplify it (piezo soundbox), and a curved block to change its pitch. Every species of wood has its own essential sound quality—cedar is scratchy and rosewood is mellow— and different shapes open new tonal ranges.

The Daxophone Consort

(2019) 4:00

A consort is an ensemble whose members all play the same instrument. Since 2016 I’ve been working with a consort of daxophonists to stretch the boundaries of what is typically possible on this instrument. Ron Shalom and Cleek Schrey each bring a personal history of string techniques to the daxophone, including the conservatory and old time music. We are currently the only known extant daxophone consort!

Masking Songs (excerpt)

(2020) 12:00

I was curious to compose with concepts I found in my research on hearing damage.

Masking Songs deals with the principle of auditory masking, in which the perception of a sound is affected by another sound. In lieu of a medical cure for tinnitus, auditory masking/suppression is one of the primary means for attenuating the perception of phantom sound. This is explained by the “critical band” principle, a psychoacoustical concept which describes ranges where sounds can interfere with each other. However, in people with hearing damage, critical bands are shifted or completely absent. This phenomenon is emphasized with tinnitus, which after much experimentation, has been proven to not respond to the critical band principle, unlike all sound in the acoustic world. In Masking Songs, I applied these principles of neuroscience to a variety of notation techniques and improvisatory strategies. The effect is a constantly shifting state of foreground and background, in which instruments in the world of the piece veer from signal to noise constantly.

This piece was composed for two ensembles playing together: Science Ficta, an group of viola da gamba virtuosi, and my own Daxophone Consort. The reedy sound of gut strings blends well with the mammalian cooing of the daxophone. Both instruments are capable of mimicry, harsh noise, and luscious resonance.

Click here, or on the picture below, for the score!

2) Composing the Tinnitus Suites

Composing the Tinnitus Suites: 2020 (excerpts)

(2020) 3:52

I want to compose music that makes tinnitus desirable rather than hated or feared. I do not want to get used to my hearing damage—I want to use it.

During a residency in 2011, I created a system of tensioned twenty-foot long piano wires activated by mixer feedback; I could sustain its tone infinitely, using guitar pickups and pressure transducers to coax the strings into vibration. I called it Lady’s Harp, named in tribute to Ellen Fullman, Maryanne Amacher, and the ancient Greek Aeolian harp, whose strings are set into vibration by the wind. I have made five iterations of Lady’s Harp, and in each version I connect the strings to the walls or floors, turning the room into the instrument’s resonant cavity. Once I showed the piece to a neuroscientist, and she remarked that it functioned as a mechanical model of the inner ear. I had stumbled upon the perfect vehicle for Tinnitus Music.

- transducer detail (2014)

- installation (2014)

- freestanding version (2014)

- pickup detail (2014)

- freestanding version (2014)

- installation (2012)

- transducer detail (2012)

- installation (2012)

Duet with Ellen Fullman

(2016) 08:00

This version of CTTS was presented in Philadelphia, PA, Fall 2016, as a part of a project grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. It showcases a semi-improvised, collaborative composition made by myself, and Ellen Fullman, inventor of her own system of long strings—she is actually one of the artists I paid tribute to with the name of my instrument, “Lady’s Harp”. In this collaboration, I wanted to do two things, first, showcase a synthesis of different instruments that use similar material, long vibrating wires and harmonics from them. Secondly, I wanted to examime what might happen if tinnitus disturbs this ecosystem. Fullman does not have hearing damage, and in a sense, I wanted to ask her music if it might be challenged or expanded by including the dysfunction of tinnitus in her orbit.

Composing the Tinnitus Suites: Mise-En Transcription

(2015-2016) 37:00

Composing the Tinnitus Suites is an ongoing series of work which explores the aesthetics of hearing damage. The aforementioned Lady’s Harp is the dark star of this music’s universe—most of my Tinnitus Music orbits around it in some way or form.

This piece is a transcription of an earlier recording from the Tinnitus Suites saga, which I created on the Lady’s Harp in 2011. After being commissioned by ensemble mise-en, I was curious whether I could make work in the Tinnitus Suites project, but without needing to do a site-specific sound installation—using the sounds of the Lady’s Harp without the burden of setting it up.

Using Fourier analysis, I approximated the harmonic content of the Harp’s strings and transcribed it for the six instrumentalists of ensemble mise-en. It occurred to me that this work could have been done more quickly with a computational process, but I did it all by hand, and savored the chance to pore over each measure, and decide what overtones should be allocated to each instrument. Thus the ensemble only plays what I was able to hear.

This piece is always played alongside tape accompaniment in loudspeakers.

Click the image, or this link, for the score!

This piece was premiered as part of Composing the Tinnitus Suites: 2016, a 4-part concert series about the aesthetics of hearing damage, which was supported by a Performance Project Grant by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. I was the lead composer and director for this concert series. The following video is an excerpt from the piece’s premiere, at The Rotunda in West Philadelphia.

3) Diegetics / Light to Sound

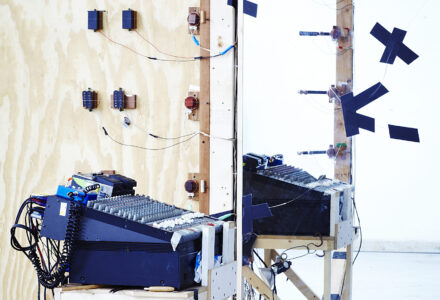

Solar Sounders

(2017-22) 02:10

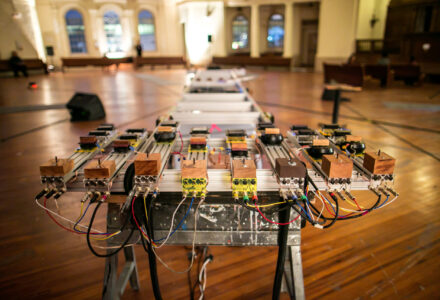

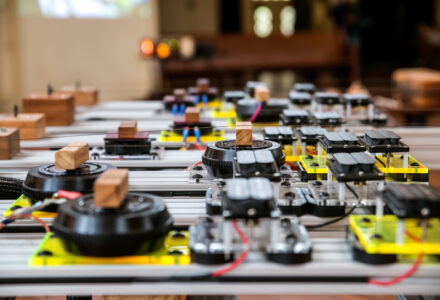

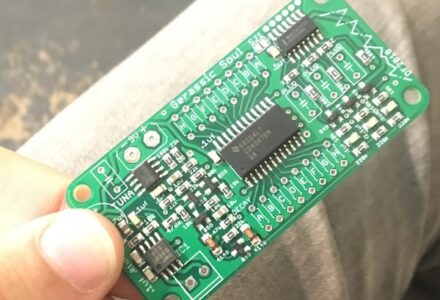

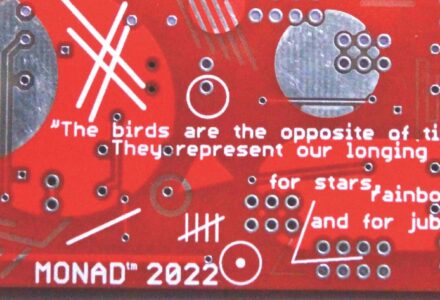

A Solar Sounder is a synthesizer played by sunlight—no batteries, and no knobs; instead, its speaker output is governed by sunlight, powering an internal synthesizer designed to work with ever-fluctuating power source. By itself, a Solar Sounder by itself is a crude machine, but in a group, they come to life, twittering away merrily, their songs changing as the day passes. I join a larger history of artists doing creative things with solar power ever since this technology became publicly available.

The sculpture of Solar Sounders happens on a micro and macro level. First, it involves the construction of hollow, resonant boxes, and the configuration of them in light and shadow to produce their desired sonics. But even before the boxes are built, transistors must be arranged on circuit boards to produce unique instrumental voices, and their voices must be tuned to different ranges to blend into the large ensemble

It’s important to note that Solar Sounders is a community driven project—reflective of what many creative designers can do with a solar panel, a driver, and a circuit board. Many have designed their own circuit boards.

WHAT YOU SEE IS WHAT YOU HEAR: TIMES SQUARE (excerpt)

(2010) 10:52

I went to Times Square with some homemade light microphones, and listened to the light waves. Many electronic lights are actually flickering off and on faster than the eye can see. In the place of a normal microphone, the photodiode lets us hear this flickering as pitch. What you see is what you hear, with no special effects or processing added. I don’t usually like being in a place like this, but the sound camera has a transformative power, like the skateboard, which turns the parking lot from urban wasteland to paradise.

i can’t handle your twisted party bullshit

(2014) 12:59

oscilloscopes, photodiodes, voice

One day at my workbench, I realized that the green CRT bream of of my oscilloscope is a very stable sawtooth waveform. I used my photodiode pickups to sonify this signal, and then built an entire synthesizer system out of four oscilloscopes and a mixer. By sending the same signal into both mixer & oscilloscope, a feedback path is made entirely in the domain of light, between the screen of the CRT and the photodiode microphone. The oscilloscope shows its own sound, and as I manipulate it, I learn from its visual language in order to predict its music. I send my voice into the oscilloscope beam, which translates it into light and then back into sound once more.

I wrote about this instrument for the 19.2 Sound and Light edition of the wonderful Canadian Journal, eContact! https://econtact.ca/19_2/fishkin_oscilloscope.html

Pendulum Music (Steve Reich)

(2014) 10:54

Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music is a classic feedback piece from the early days of minimalism and process music. Old pieces of the avant-garde can seem dusty, but feedback, which is unique in each instantiation and each resonant cavity in which it is found, should never actually get old. I wanted to add another wrinkle in the story of this piece, and so shifted the medium from sound to light. Instead of speakers, I use oscilloscopes, and instead of a microphone, I use homemade light microphones made from photodiodes. Besides this, the basic structure of the piece is unchanged.

thanks for your kind attention!