Daxophone

THE DAXOPHONE

I was drawn to its uncanny vocal timbres, that sound somewhere between a badger and a cello.

My entry into experimental music started with the daxophone.The daxophone, created by Hans Reichel, is a more elegant construction of the instrument every child discovers when they put their ruler off the edge of their desk and pluck it: BOING! When that ruler is played with a cello bow, it produces a much different sound: a very vocal, vowel-ed tone that could easily be mistaken for another instrument or animal. One cannot buy a badger-cello, so I learned to build my own. I noticed that every piece of wood sounded unique, and I could control the instrument by altering its shape. I built hundreds of daxophones, each with its own melodic voice. In the daxophone I found a gurgling court jester that could laugh along to any music, and I played it loudly, from orchestra halls to basement shows.

The daxophone is literally only wood—no strings or air columns. Every change you make to the wood changes the sound. The essence of the instrument is a vibrating tongue, anchored at one end. The other parts of the instrument are tools to resonate that tongue (bow), modulate the tongue’s length (the curved block of wood known as a “dax”), and a stable surface sound body to amplify the tongue’s vibration (soundboard with piezo microphones). In fact, all you need to make a daxophone is a ruler, a clamp on the table, a bow, and a guitar slide. Here’s a summary of the different approaches I’ve taken to it, since 2005.

RECENT EXPERIMENTS (2019-2022)

For big daxophone updates, check out the new page for The Daxophone Consort! This ensemble is the world’s only one of its kind, dedicated to realizing new contexts for this instrument. We have been very active for the last three years, with lots of recordings, performances, and a very special commission.

Since 2018, my daxophone store has been open. After over a decade of experimentation and refining my craft, I decided to start selling these instruments. Check it out! There are lot of new soundbox concepts there, such as the apprentice model.

DEVELOPING DAXOPHONE CRAFT (2017)

In 2017 I was given a special opportunity to push my work with the daxophone even further. I was awarded a fellowship by The Center for Art in Wood’s Windgate ITE International Residency Program, which consisted of a 8-week long, generously funded residency in my hometown of Philadelphia, along with 5 other woodworkers, and even a photojournalist and scholar. I lucked out, too, because the photojournalist was my best friend, Samuel Lang Budin. I was set in dialogue with talented woodworkers, furniture designers, and woodturners, and we worked alongside each other for 8 weeks. The residency culminated in a group show in Philadelphia at the Center.Often, the world that I inhabit is full of musicians, and I am the only woodworker in the room. During the residency, this situation was totally inverted—I was the musician, and I was in the company of consummate masters who used wood as their material. I do not have any conventional training in woodworking, so I was was inspired and encouraged to focus new attention on the craft of my instrument building. Beyond that, I wanted to experiment with many ideas I’ve had about the daxophone for years.

NEW STARSHIPS

These are my newest daxophones. Since 2015, I’ve developed a personal approach to the daxophone soundboard, the “starship”, consisting of a doubleneck soundboard with a sculpted seat, for easy set up in contrast to the Hans Reichel tripod model. The ergonomics of this soundboard were always inferior to the Reichel tripod, however. So, finally, I was able to update my design with an adjustable hinge, which is locked in place by two clamps and a simple sliding bracing mechanism machined from steel. For more information about the starship—the history of this model is detailed below!

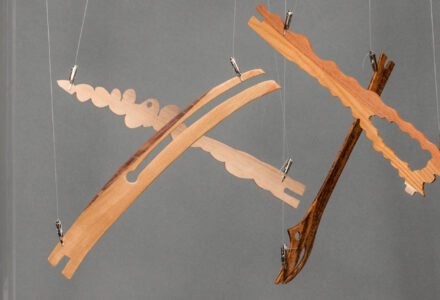

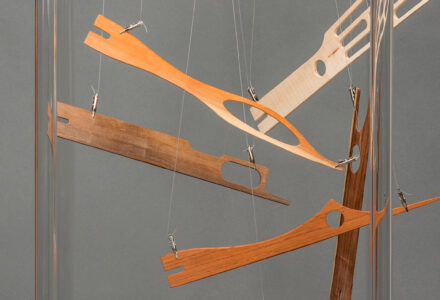

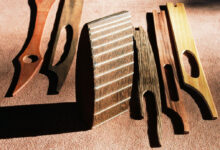

76 NEW TONGUES

One major undertaking was to build a huge bundle of daxophone tongues. The tongue is the soul of the daxophone, and I’ve built a great many in my 10 years of building daxophones, but I had never systematically explored the different shapes in Hans’ font, Daxoph. Beyond that, I was able to try different building styles and get a feeling for them. For the first time, I had access to a CNC machine, so I designed many unique tongue shapes, as well as copied exactly some of the Reichel shapes that had eluded my untrained hands for years. In contrast with the CNC machine, I also spent many days cutting tongues on the scroll saw—the daxophone luthier’s best friend. A scroll saw offers a degree of improvisational creativity, and a superior edge right off the tool. Sometimes, I would switch from the CNC to the scroll saw in the middle of the process. Some of these shapes didn’t sound good at all! It can be hard to predict what tongues were truly stellar instruments. I labored painstakingly over some tongues made from exotic hardwood, and was surprised how boring they sounded. Other tongues began as sketches in humble lumbers, yet ended up sounding fantastic.

- most of these are scroll sawn.

- the fancy group

- cartoon group

- the A and O group

- the inlay group

- i didn’t name this one

- most of these are cut using a CNC.

- the A group

The above “gardens” are grouped somewhat thematically. I made a study out of the “A”, “B”, and “O” shapes, using handtools and computer design to vary subtle aspects of the design, wondering if I could induce appreciable sonic changes. One garden showcases my experiments in 2.5-D inlay, which were mostly sonic failures, save for an incredible tongue made from cocobolo and pine! One garden is made of totally improbable shapes, the “cartoon group”—I wanted to just improvise with the design, and free myself of the restraint of making playable instruments. Some groups mix CNC and scroll-saw work, to show the warm human errors of my technique, which I came to favor by the end of the process. These pictures do not show the micromovements of dax-design—many tongues are radically different in sound because of subtle bevels on their edges, or whether they are finished by a scraper, sandpaper, steel wool, or scotch brite. Every wood calls for a different approach. One such revelation—mulberry responds better to a sharp handplane rather than sandpaper, which dull its chatoyant fibers! A note about the display choice—these vitrines were given to me by the Center for Art in Wood, and had been previously used to display fishing lures!

“THE STUDENT MODEL”

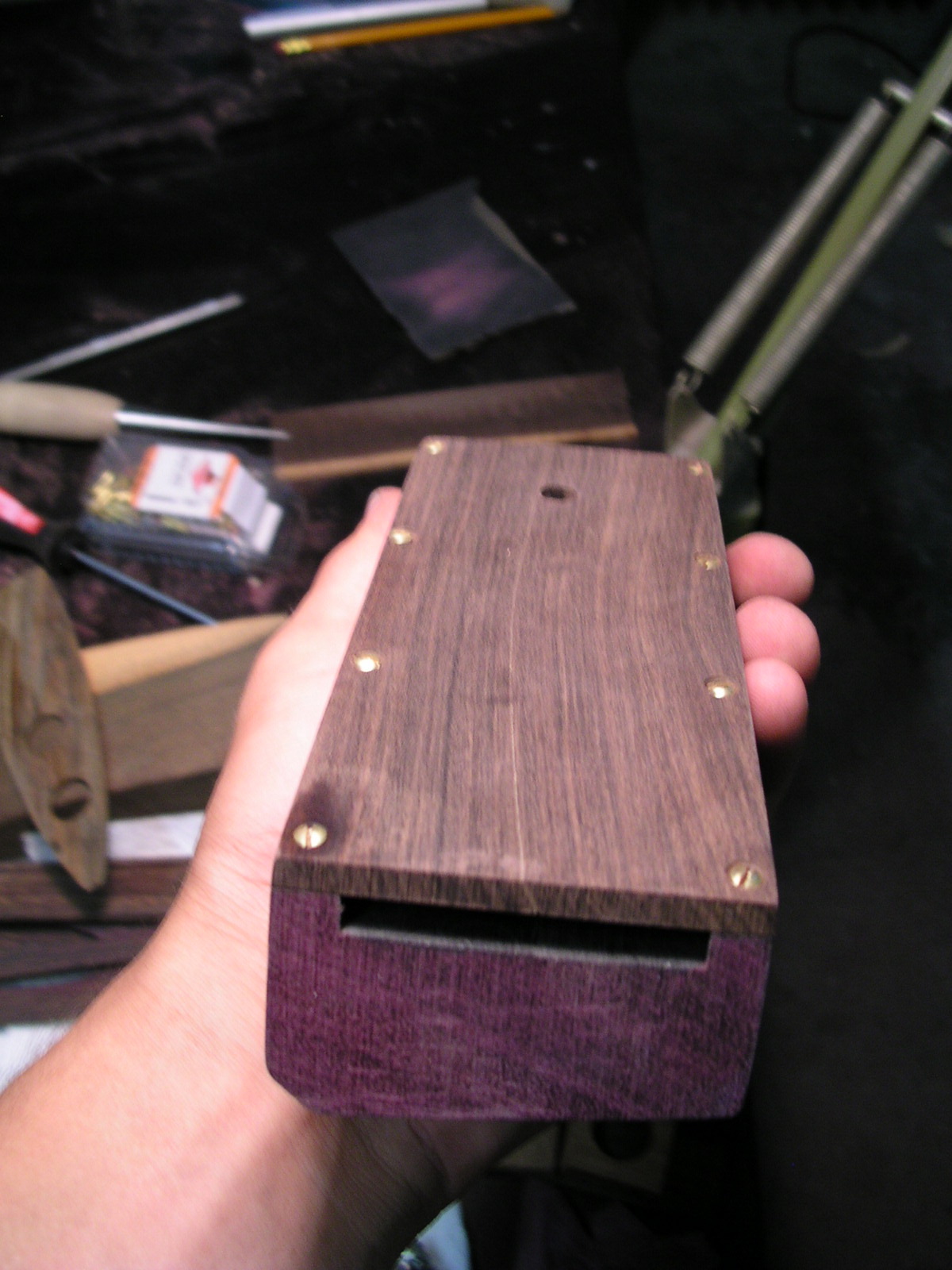

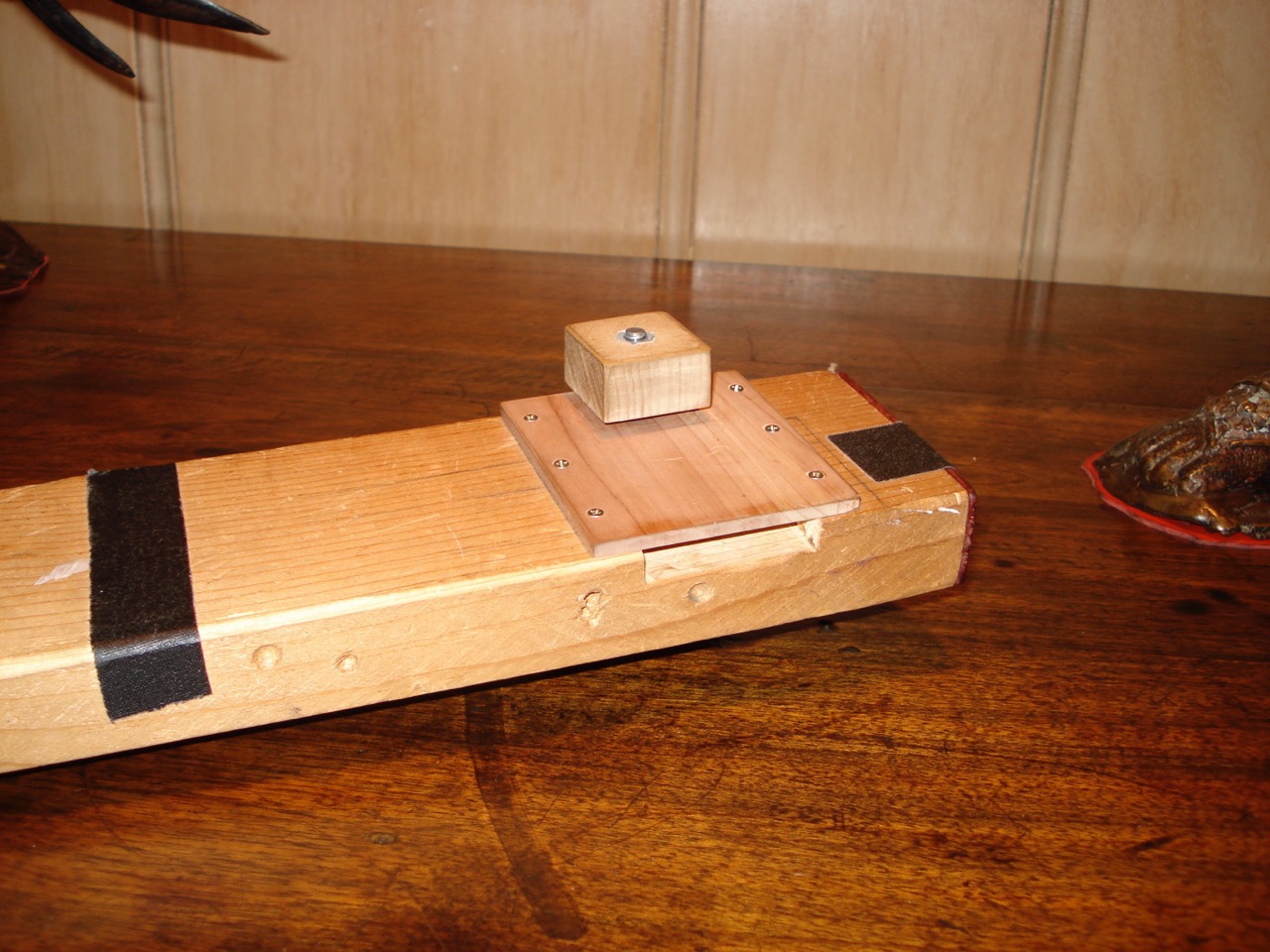

One thing I wanted to try during this residency was to develop a simpler approach to the daxophone soundboard, which is by far the most labor intensive part of my design process. Hans Reichel already developed this approach decades ago, but I had never seen it documented or recreated anywhere. So this was a chance to creatively think through daxophone history, though it hasn’t been articulated or replicated since 1987. I delighted in having a chance to prototype this approach, which was made totally intuitively, with improvised measurements and an absolute minimum in hardware. I was inspired by the principle of the bandsaw box for this one—and the fancy clamp is replaced by a c-clamp. The important thing about this design is that it works beautifully, even though it is quite crude compared to my other designs. I built four soundboards, trying different woods and different piezos. (mostly, the instruments sounded the same!) To display these instruments in the gallery, I built a quick table from a huge chunk of wet oak, which I stained with steel and vinegar, and cut into a large X, to facilitate an ergonomic installation—the idea is that up to four daxophonists can set up facing each other! You will see such a formation in the above picture gallery; the New Perplexity Daxophone Quartet convened for a concert to inaugurate the gallery opening!

Read below for my dax history in reverse chronological order!

THE STARSHIP

My personal contribution to the daxophone is the “starship” soundboard—an elaborately carved, comfortable surface which serves as both the resonant soundbody and the stabilizing table. Unlike Hans Reichel’s tripod version, you sit on my soundboard, which keeps the whole instrument perfectly rigid. This rigidity is actually quite essential to the instrument, as the bow exerts a lot of force against the tongue during play. The soundboard is amplified with a piezo microphone, which allows the bass voices of the daxophone to be heard. A lesser contribution is the doubleneck, which isn’t so novel—multiple tongues were first explored by Glenn Wyllie in his “totem dax” (2000). Since I began performing on the daxophone, fascinated audience members would muse “you could make a soundboard that holds multiple tongues!”. I started building doublenecks mostly as a way of shutting them up. I have always loved the minimalism of a one-tongued daxophone—infinite worlds of sound can be found in just one tongue!

The name, the “starship”, comes from Peter Blasser, my colleague and friend, who builds exquisite, radical synthesizers encased in wood. PB is an inspiration, and his work challenged me to step up my lutherie game, to make daxophones from beautiful lumber, rather than pine that I found in the trash. In fact, Peter donated much of the wood that I used for my first batch of soundboards from his lumber-pile—a boundless gift of generosity and encouragement. After I had began the initial stages, I showed Peter the prototype soundboard. He said, “it looks like the Enterprise!”

- the starship in flight

- daxophone parts (2016)

- the starship quartet (2016)

- dax mess

Peter’s lumber gifts were exclusively local: mulberry, catalpa, hackberry, juniper, sycamore, maple, cherry, sassafras, walnut. Salvaged exotics: wenge, cocobolo, bocote, mpingo, osage orange, redheart, teak, lignum vitae, bloodwood, and purpleheart, and on and on. In my breadboard style laminates, the woods of the starship are not so sonically critical. Subtle differences can be detected. However, in tongue choice, the tonal variety is staggering. It should be obvious that a piece of rosewood sounds completely different from oak. I do not buy imported exotic lumber on principle, but due to the small size of a daxophone tongue, I have often found excellent tonguestock waiting for me in the dumpster of many woodshops over the east coast.

New Perplexity

I began these starships in the twilight days of my master’s degree at Wesleyan, and finished them 6 months later. In 2016, I gave three of these soundboards, daxes, and 6 tongues each to my daxophone quartet: Dina Maccabee, Cleek Schrey, and Ron Shalom. I gathered these musicians in 2014 to develop a transcription of John Cage’s Ryoanji. Because they are classically trained string players, they were able to learn the daxophone rather quickly. I was moved by their unique voices on the daxophone, and I vowed to eventually build them their own instruments so they could continue to experiment. The world always needs more daxophone players, especially players of this high caliber! This band would eventually evolve into The Daxophone Consort—these pictures show the cute discovery and maiden flight of my starships in the wintry months of 2016.

- Ron Shalom, receiving a daxophone

- Cleek, with quartet

- Quartet!

- some tongues

- ron, dina

- rehearsing

- i am a soundboard.

- daniel, cleek

HISTORICAL

The daxophone was the first instrument I learned how to build—my gateway drug into a world of weird sounds. I stumbled upon this instrument for the first time in 2004, while surfing the web for new sound ideas for a class on John Cage, and I was instantly smitten. At the time, one could not buy a daxophone anywhere, so if I wanted to play this instrument, I had to build it myself. My first daxophones were very primitive; I fastened scrap wood to tables with c-clamps. At this point, my playing technique was very animal—almost intolerable—although I confess a certain nostalgia for these days of unbridled enthusiasm in untuned mammalian cacophony.

Luckily, however, I soon found a daxophonist in the New York area who was willing to teach me. Mark Stewart, electric guitarist of the Bang-on-a-Can All-Stars (and Paul Simon), became my instrument building teacher and mentor. In my first few lessons, Mark helped me build my own daxophone, which was a variation of his design, the “butt daxophone” (Because you sit on it…with your butt). I built several of these soundboards over the years, each with its own unique tonal or structural qualities. These soundboards were all made from scrap wood. While they were perfect for a punk show, these butt-daxes were not so comfortable to sit on, and they looked like garbage. But they sounded great!

- wooden tongues (2009)

- some tongues (2009

- I made this daxophone for Eric Archer in 2009!

- daxophone soundboard (2009)

This was a nice set of pictures taken by Eric Archer. I made him a daxophone as a trade for a sound camera and drone matrix. This turned out to be one of the nicer butt-daxes, as I made it for another person, so I was very careful. It was a spiritual exchange, and his sound camera led to my long investigation into the vibration behind lightwaves.

THE REICHEL TRIPOD

In 2006, I visited Hans Reichel! The result of this visit was my very own Reichel style tripod—a little bit larger than usual, which resulted in a unique tone. I swapped the soundboard twice over the years, from the original rosewood, to cedar, and finally back to rosewood again. These are just a couple of pictures from this influential workshop: see more on my blog!

- the tripod

- in progress.

- the tripod (rosewood soundboard)

- Hans at work

NOSTALGIA?

Here are some old, old pictures, which show the earliest experiments from my daxophone days. I share these as important evidence that the daxophone is a very basic concept, and needs no refinement to work properly! You can see my first instrument, some early tongues, and my first doubleneck! I also made a bunch of tongues as a gift to Mark Stewart.

- The first doubleneck! (2013)

- the earliest daxophone (2005)

- performance still

- some early tongues (2006)

- as dandelion fiction (2011)

- daxophone wall for Mark Stewart (2009)

- The second soundboard (2006)

- the “travel dax” (2010?)

TECHNIQUE

I stuck this section at the end. Any aspiring daxophonists wanting to develop and improve their technique might take some of these suggestions. For what it’s worth, I use a cello bow and hold it with an underhand grip adapted from the playing technique for the viola da gamba. Later I discovered most “contemporary” daxophonists (haha) use a german kontrabass bow, but the cello bow works out fine for me! I really enjoy using my fingers to control bow tension—it helps with staccato passages. Try using the dax in every possible angle—the pitch range changes as you rock it top-to-bottom, not just left-to-right. Do not oil the tongues (duh)—sandpaper is useful for finishing the tongues (obvi), but also consider using steel wool and a card scraper! The sound is different. None of these pictures reveal the sharpened edges or bevels which are crucial to honing the bow response. Filing and planing results in these details. I cut most tongues on a scroll saw, which, when used effectively, has the advantage of leaving a perfectly polished edge, needing almost no sanding before the needle file is implemented.

DO YOU SELL DAXOPHONES?

please visit the store, link above. ____^

Photos by Ben Tran, John Carlano, Dina Maccabee, Josh Carrigan, and Daniel Fishkin